It's hard to write story for a massively multiplayer game. You need story that can be played by thousands of people. In some cases they're playing it simultaneously, and in other cases they're playing it months or years apart. You want players to feel like their efforts matter, but you have to deal with the oddness of having thousands of people each being the one who permanently killed that undead space god. Sometimes more than once.

We're wrestling with these issues in designing our browser-based hacktivism game, Exploit: Zero Day. We now have enough alpha testers that people are asking for advice in-character and running into questions about how they should maintain verisimilitude in this weird story environment.

Games have used an array of approaches to resolve this issue. Here are just a few.

Casual

This tends to be the default in a lot of MMOs like World of Warcraft. You can kill the same character repeatedly; bosses just wait around like amusement park employees for the next batch of players. Nobody particularly worries about how this is possible, because the game doesn't present itself with too much verisimilitude.

No Big Consequences

The player never really defeats anyone important or enacts major changes on the world. They just fight waves of faceless enemies, or the major adversaries use the same approach every time and are only driven back, not defeated permanently. This approach can steal a lot of weight from the player's personal story, as it can feel like nothing they do matters.

Emergent Story

Best displayed by Eve Online, the emergent story approach uses a deep, complex simulation that lets players' rivalry create interesting stories without any developer-authored narrative. Eve's best-known stories are the result of player corporations going to war or struggling for resources. The game does have pre-authored story missions, but the focus is on the story that emerges out of player interactions.

Genericized Story

Players have very similar experiences to each other, but it's not specified that they're exactly the same. Fallen London does this with a lot of its story. You romance "a charming young jewel-thief," not someone with a specific name. You befriend the "Repentant Forger." This fits the game's Victorian penny-dreadful theme and allows the player to pretend that they're hanging out with a different "honey-sipping heiress" than the next player, but this approach prevents you from being too specific or fleshing characters out in great detail.

Making all your story procedurally generated is a cousin to the approach. Giving characters and places random names is just another way of making content generic enough to maintain the illusion that it's not all the same.

Instanced Worlds

There's some sort of in- or out-of-game conceit that results in the players performing tasks in personalized universes. Myst Online: Uru Live uses this approach. It takes advantage of its dimension-hopping presence by giving each player their own parallel version of story-focused ages. This is a fine way of handling it if your fiction supports it, but games set in less fantastic worlds have trouble making this feel plausible.

Our Approach

Early in development we considered using the genericized approach, generating names and modifying story details enough that each player got a personalized version of the story. However, we decided that this would require too much development effort and limit our story too much. We value our story too much to take a casual approach or avoid consequences, and our systems don't allow much emergent story at the moment.

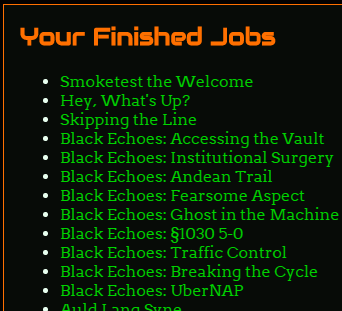

In the end, our style depends more on trusting the players and encouraging the sort of techniques you see in tabletop roleplaying games or dramatic improvisation. Our story is written as if our world is instanced. Players work with named characters and take part in unique one-time events where they take down a rogue cop or falsify government documents. We don't have any in-universe explanation for this conceit; instead, we ask the players to play along.

In cases where the story requires a suspension of disbelief, we're asking the players to facilitate each other's experience. Players who have been through a story can act as mentors or emotional support for players going through it the first time. This way we can have dramatic story with consequences focused on a single player character, but we rely on our trust of the players and the community standards we're establishing to make that mesh with the wider multiplayer experience.

To read how we've established our standards for this sort of situation, check out our post on Exploit: Zero Day's forums: "How to Share the EZD Story World." This document is now linked from our code of conduct, and should serve as a point of reference as more and more players sign on.

Does this seem interesting? You can get on the list for a free access code to Exploit: Zero Day's closed alpha test by signing up to our mailing list. This month, all mailing list members will get an extra code to give to a friend! If you're media or a streamer, get a key now through our distribute() page.

View on YouTube

View on YouTube